Black history is tightly woven into the fabric of Oklahoma. Learn about the profound impact African Americans have on the state’s military, frontier, Western and modern history.

Pre-Statehood

The Trail of Tears brought many African Americans into Indian Territory, when thousands of Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands between 1830 and 1842. Many who made the journey were enslaved by Native Americans, but a group of 500 agreed to move to Indian Territory in exchange for their freedom. Known as The Gullah, a west African enclave that lived side-by-side with refugee Seminoles in Florida, this group of 500 made the journey as free men. Those that survived the trip either remained enslaved until treaties between the U.S. and American Indian tribes were ratified, or lived among the tribes as Black Seminoles.

Learn More: Visit the Seminole Nation Museum for a collection of documents relating to Black Seminoles in the museum’s research library. This museum also features exhibit space and an art gallery, as well as photos and maps of original land allotments.

In 1889, President Harrison opened up Indian Territory to settlement. Soon afterward, a variety of prospectors descended on what would become Oklahoma for the territory’s famous land runs. While forced to the back of the crowds along the starting line and only allowed to claim land not already taken by their white counterparts, a group of Black ‘89ers were able to begin homesteading along Oklahoma’s frontier.

Military Mettle

During the Civil War, many freed slaves joined Union forces stationed in Indian Territory. In October 1862, a group of freedmen and escaped slaves from Arkansas, Oklahoma and Texas formed the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry, the first black regiment in the Union Army. African American, Native American and white soldiers fought side-by-side in 1863 for one of the first times in history at the Battle of Honey Springs. A decisive battle, Honey Springs essentially ended Confederate dominance in the West.

Learn More: Visit the Honey Springs Battlefield Historic Site in Checotah to view the 1,100 acre battle site, which includes six walking trails and over 50 interpretive signs. Reenactments of the battle are staged every third year.

After the Civil War's conclusion, the U.S. Army continued to form all-Black cavalries and infantries. During this time, Buffalo Soldiers (named as such by Native American tribes) comprised 10% of the army’s western forces (including Oklahoma). These Black soldiers played a pivotal role along the frontier – they laid telegraph lines, mapped uncharted territory and protected citizens, all the while keeping conflicting forces like outlaws and Boomers at bay. In total, 18 Buffalo Soldiers earned medals of honor, the U.S. military’s highest distinction. In Oklahoma, Buffalo Soldiers served from Forts Cobb, Arbuckle, Sill, Reno, Gibson and Supply.

Learn More: Visit Fort Sill, Fort Gibson, Fort Reno or Fort Supply to walk in the footsteps of the Buffalo Soldiers who served there. Fort Sill National Historic Landmark & Museum features a special walk-through exhibit in honor of the soldiers, while Fort Reno’s cemetery holds a number of Buffalo Solider graves.

All-Black Towns

Cheap land in Indian Territory coupled with systemic racism led many African Americans to settle in exclusively-Black towns. After the Civil War, Black community leaders recruited freed slaves to these All-Black settlements by advertising a promised land of business opportunity, wealth and safety. Between 1865 and 1920, approximately 50 All-Black towns were settled in Oklahoma. Although the number declined after the Great Depression, 13 of these original settlements are still incorporated in Oklahoma today.

Learn More: Visit Boley, Oklahoma, which was “the most enterprising, and in many ways, the most interesting of the negro towns in the U.S.,” according to Booker T. Washington. Head to the Boley Historical Museum and see the Farmers & Merchants Bank, the first Black-owned bank to receive a national charter.

Enjoy blues music during the Dusk ‘Til Dawn Music Festival at the Down Home Blues Club in Rentiesville, an All-Black town founded in 1907. Head over to Langston University to visit the only historically Black college in Oklahoma. While there, check out the Melvin B. Tolson Black Heritage Center, which houses several Black newspapers and African artifacts.

The Old West

A distinct Black cowboy culture emerged after the Civil War, as African Americans in Indian Territory became everything from cowhands to bandits. U.S. deputy marshal Bass Reeves, one of the most feared lawmen in Indian Territory and an African American, killed more men in shootouts than Doc Holliday or Wyatt Earp. Cherokee Bill, whose father was a Buffalo Soldier, joined up with the Cook Gang and robbed everything from trains to banks from Claremore, Oklahoma to Coffeyville, Kansas. Bulldogging, or steer wrestling, was invented by African American cowboy Bill Pickett. Pickett performed in the famous 101 Ranch Wild West Show from 1905 to 1931 and became the first Black cowboy movie star after appearing in silent films The Crimson Skull and The Bulldogger, both of which were filmed in Oklahoma.

Learn More: Visit the Three Rivers Museum in Muskogee to see multi-ethnic heritage exhibits, from the American frontier and plan your trip in October for the museum’s Bass Reeves Legacy Lawmen & Outlaw Tour. Journey to Bill Pickett’s Gravesite to see where this famous Black cowboy was laid to rest, and tour the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum to view a variety of exhibits, including a life-sized statue of an African American cavalry bugler in full gallop.

Deep Deuce

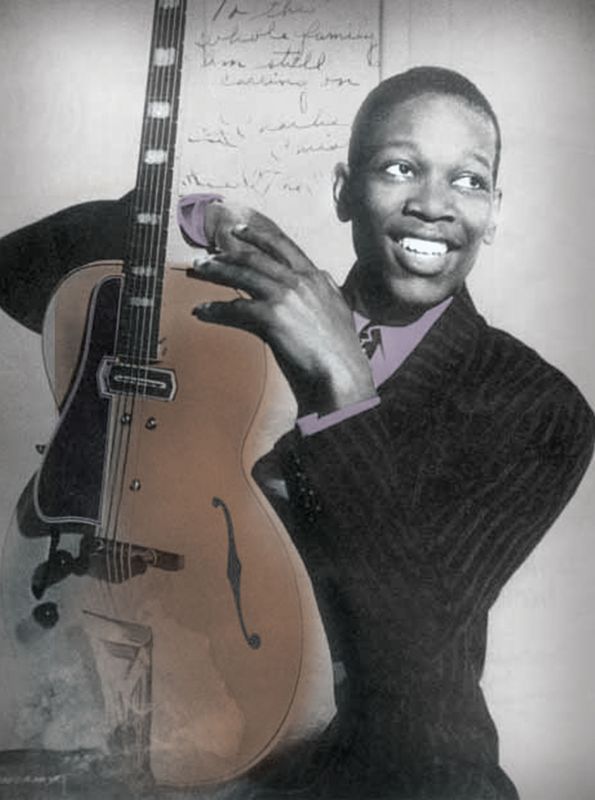

From the jazz era through the 1940s, Oklahoma City’s Deep Deuce District was a haven for nightlife and black commerce, as well as jazz and blues music. Like in Tulsa’s Greenwood District, segregation led to clusters of African American businesses, housing and art during this era. Deep Deuce, which was centered around NE 2nd Street, gave birth to Charlie Christian, an electric guitar master and first big band guitar soloist, and Jimmy Rushing, the famous blues shouter who sang with the popular Count Basie Orchestra. Ralph Ellison, the first African American to win the National Book Award for his 1952 novel The Invisible Man, also grew up in Deep Deuce.

Learn More: Visit the Deep Deuce District and walk the same streets as Charlie Christian and Ralph Ellison – just don’t forget to stop for cocktails and good food at Stag Lounge. Hear live jazz music at the Charlie Christian International Music Festival in Lawton or head to Tulsa’s Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame, which chronicles the history, evolution and influence of jazz in Oklahoma. Oklahoma City’s Black Museum & Performing Arts Center features contemporary work by local African American artists, as well as rotating exhibits.

Civil Rights

Oklahoma was not immune to the battle over civil rights – racism persisted at the turn of the 20th century and was most evident in the Greenwood District of Tulsa. Strict segregation laws kept the majority of Tulsa’s African American population concentrated along the city’s Greenwood Avenue. It was here that Black Wall Street thrived with a variety of successful businesses, newspapers, artistic venues and churches. In 1921, racial tensions within the city erupted into one of the worst massacres in U.S. history. During the Tulsa Race Massacre, over 40 square blocks in Greenwood had been reduced to rubble.

Learn More: Today, the Greenwood District offers a variety of museums and centers honoring and preserving the legacy of the neighborhood. Opened in 2021 on the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre, Greenwood Rising is a state-of-the-art history center that tells the story of Black Wall Street through immersive exhibits and interactive galleries. In the same area, the Greenwood Cultural Center features an African American art gallery, historical exhibits and neighborhood memorabilia. Head over to Reconciliation Park for outdoor displays depicting Oklahoma’s Black history, from slavery to the rebuilding of the Greenwood District.

The fight for equality in Oklahoma continued well into the mid-20th century. In 1946, Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, supported by Roscoe Dunjee (editor of Oklahoma’s only Black newspaper at the time, The Black Dispatch) and the NAACP, applied to the University of Oklahoma’s law school but was denied based on race. After taking her fight to the U.S. Supreme Court, Fisher was finally admitted in June 1949. Fisher’s case paved the way for 1954’s landmark ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education court case, which ordered integration over failed “separate but equal” segregation policies.

Less than a decade after Fisher’s case, Clara Luper led one of the first sit-ins in the nation at Katz Drug Store in Oklahoma. In 1958, Luper and a group of NAACP youth took seats at Katz’s lunch counter and ordered Cokes. The group was continually denied service, but they kept returning every Saturday for weeks. Katz Drug Store, which was formerly located at the corner of Main and Robinson, finally relented and opened their lunch counters to African Americans in 38 stores across four states. Luper is still regarded as one of Oklahoma’s most important civil rights activists.